The Piano Teacher (2001), Michael Haneke

On one hand, it can be viewed as an examination of the various facets of love; on the other, as a feminist narrative about a woman escaping internal and external pressures. One certainty: anyone seeing romance here cannot be entirely sane.

The use of rooms and staircases as thematic devices is particularly intriguing. As suggested from the first scene, each order resides within its own spatial confines—a room. The desire for subversion manifests through door handles and staircases. Erika finds freedom from oppressive order in a pornographic shop’s screening room, behind heavily soundproofed doors impervious to external order—represented by her psychotic father’s Schubert and executed by her mother. Conversely, Erika and Walter’s emerging sexual relationship, a competing order, unfolds in her father’s room, where he cannot see but can hear. However, from Walter’s very first appearance, he is already excessively ahead of Erika. Her final choice involves self-harm and spatial escape. Perhaps this escape is just that—an escape; the self-inflicted stab wound could symbolize a radical, DIY approach to sexual liberation.

The Killer (2023), David Fincher

Assassination as livelihood: The nihilistic assassin cares about nothing. Dividing the world into the weak many and the powerful few, he subtly implies his membership among the latter but never overestimates his influence. Don’t misunderstand—only payment holds significance, or so he repeatedly insists.

Those pulling triggers easily mistake bullets for their own; yet the murderous intent truly belongs to others. An expert recounts a hunter-bear story as a veiled warning about shared undertakings and concealed desires behind repetitive actions. Coincidentally, the assassin has just returned from killing an animal. Facing the billionaire mastermind behind the assignment, he realizes his limitations—not due to moral qualms, but rather the futility of repetition itself.

None of the assassin’s numerous aphorisms throughout two hours directly addresses murder; separated from context, they could belong to any diligent office worker’s ethos. His girlfriend suffers repercussions because he inadvertently killed a civilian, but as the expert notes, these are merely occupational hazards. After exacting revenge, comfort comes not from revenge itself but from coffee, snacks, and a sunny recliner. No growth feels more modestly bourgeois than relinquishing professional obsession and appreciating simple downtime.

Vagabond (1985), Agnès Varda

Another distinct “gaze” from Agnès Varda. The opening scene, functioning similarly to Hitchcock’s “Rear Window,” searches through deep focus for the optimal subject. Passing by a worker gathering twigs in sub-zero weather, the camera finally settles on a frozen woman’s corpse, resurrected through witness testimonies. This nameless woman becomes many things: an embodiment of romance for a woman trapped in a dull relationship, a surrogate daughter and lost youth for a childless career woman, a sex symbol for motorcycle gangs, and a companion who understands plight for Moroccan laborers. Physically and conceptually, the vagabond is free. Her tragic fate as an incompetent homeless person is foreshadowed throughout, yet as long as the audience watches, she never truly dies. Whether to sympathize or criticize is entirely the viewer’s choice.

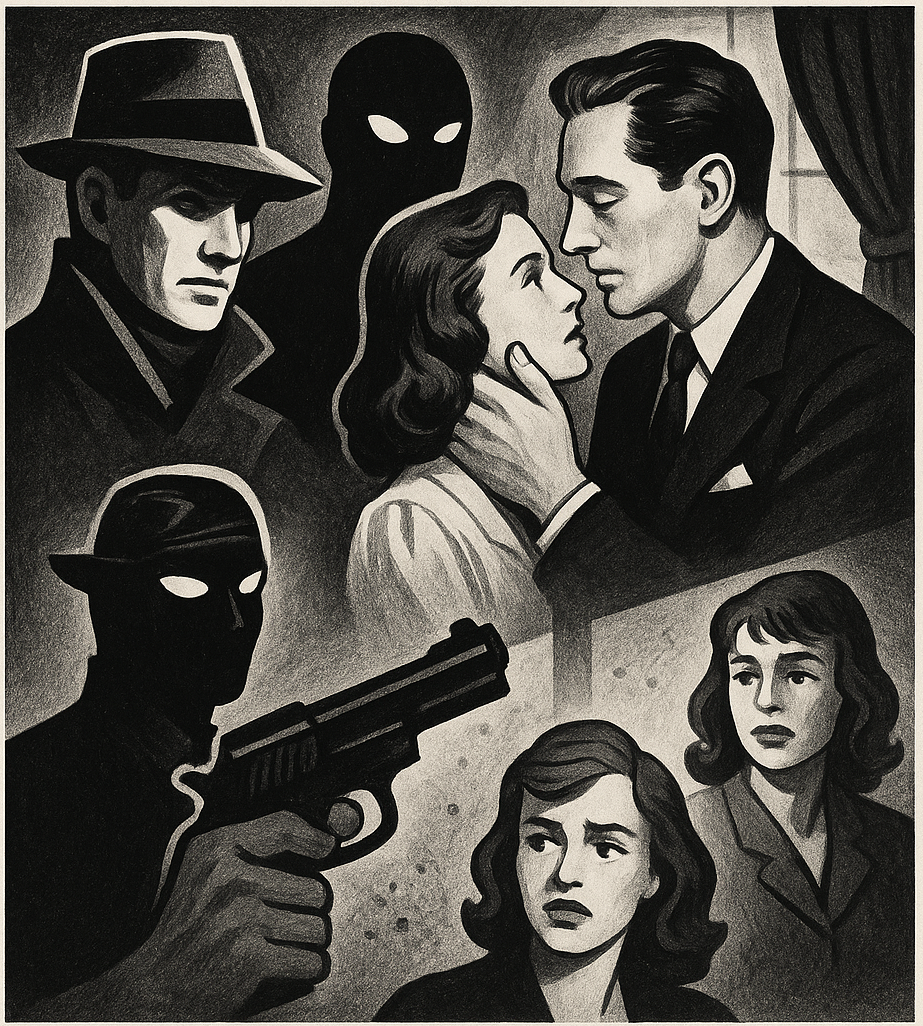

Kiss Me Deadly (1955), Robert Aldrich

A peculiar journey. Chasing names ultimately leads to abstract art and nuclear science—areas incomprehensible to the protagonist. A film shifting through multiple genre distortions might be labeled a B-movie; if so, “Kiss Me Deadly” certainly fits that category. Interestingly, despite its perplexing conclusion, the film flows naturally, devoid of typical B-movie sensibilities. Mike’s internal shift—from profit-driven private detective (reflecting common citizen greed) to one focused on protecting those close—is a typical commercial film trajectory. Encasing the confusion of the Manhattan Project and modern art within the plot creates a B-movie; yet, choosing to experience this bewilderment alongside the protagonist transforms the story into a modest citizen’s venture to conceal Cold War radiation with bare hands. While film enthusiasts later regarded it as a standout B-movie anomaly, contemporary viewers may have felt genuine crisis.

Lights in the Dusk (2006), Aki Kaurismäki

A detachment so profound that even relentless squeezing of a person until they resemble a dry rag feels devoid of sadism—existing equally between camera and subject. Hope extinguishes so effortlessly that it seems capable of re-ignition anytime. No concrete justification is needed. It has always been so. As for that kind of woman—let her live as a lifelong servant to men.